An essay written by Rose Bouthillier on the occasion of the exhibition One Once on Which Whatever What at AKA artist-run September 14-October 20, 2018.

Download the PDF

Ways of thinking

- just enough

Troy Gronsdahl used these words to describe one of his chosen materials to me. This phrasing stuck in my mind, becoming a broader notion for thinking through his practice. While at first it might appear to imply offhandedness, or even a lackadaisical work ethic, neither is the case. There is a fine edge between not enough and too much. This tension is often apparent in Gronsdahl’s work; underscored, regarded and worried about. Whether through process, form, historical reference or sentiment, arriving at this edge is a delicate undertaking. It wavers constantly, impossible to hold.

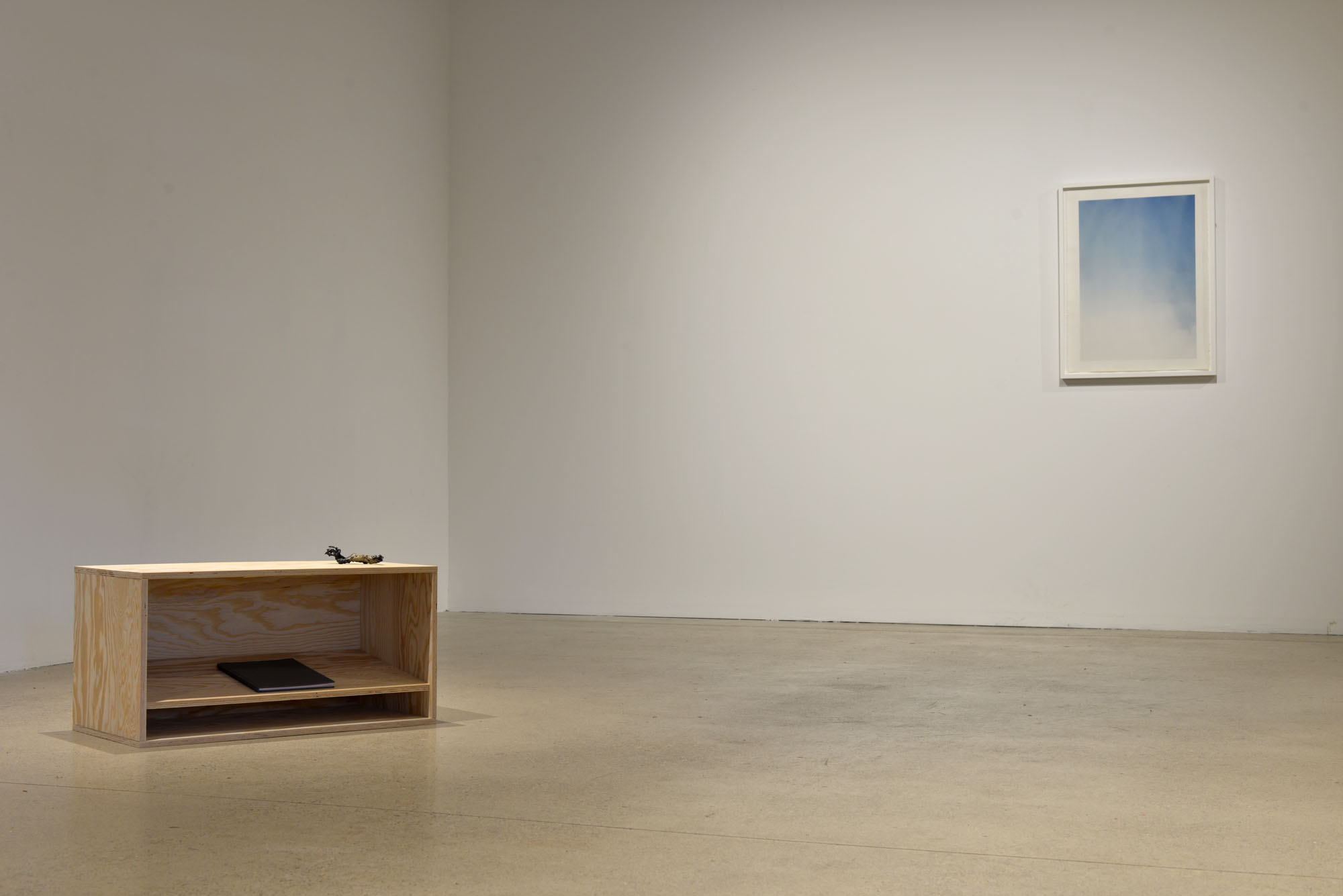

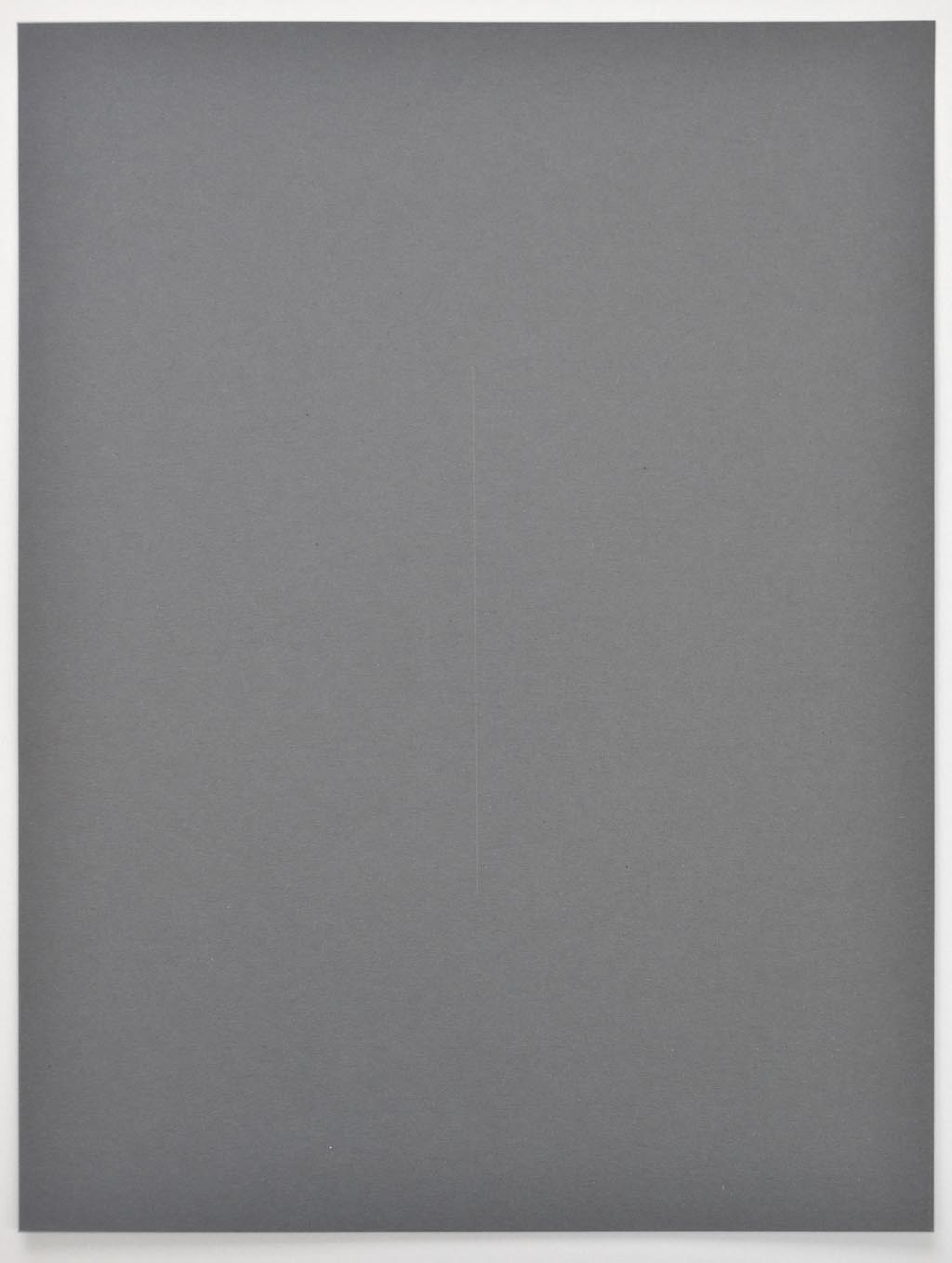

This enough sits on the surface of Gronsdahl’s ongoing series of cyanotype prints, When the cosmos aligned, if only briefly and largely unnoticed. The series started on March 20, 2015, marking the transition from winter to spring. Each print in the series corresponds with a cosmic phenomenon: most often an equinox or solstice, though recent additions include a total solar eclipse and an aphelion (the point at which the Earth is farthest from the Sun). The results range from soft, atmospheric gradations to semblances of crumpled bed sheets and haphazard sun bleaching. They alternate (often on a single surface), between evoking celestial expanse and stressing their own obstinate, unpredictable materiality.

Making the cyanotypes requires patience and attention to details: carefully mixed chemistry, cleanly taped edges and an even coat, free of debris. The prints are exposed in the artist’s Saskatoon studio, absorbing ambient light for a 24-hour period, roughly from midnight to midnight. Gronsdahl meticulously sets the conditions, but the medium is hard to control, moving from wet to dry to wet to dry, with all of the attendant molecular and material shifts. A number of variables affect the outcome fluctuations in temperature and humidity, proximity to windows and other objects in the studio, clouds and particulates. In appearance, the cyanotypes echo the spare ambiguity of monochrome painting, repeating like exercises in looking at blue. Minimalism starts from a point of austerity (even as imbued with a range of aesthetic, philosophical and spiritual propositions). Reductive. Rigorous. Clear. Gronsdahl takes a genre rife with repetition and control, and floods it with happenstance and sensitivity.

While the series is driven by cosmic events, only the artist knows if the exposures took place when their titles claim. Other than large shifts in the intensity and duration of sunlight, there is little to indicate the season of their making, let alone the precise day. There’s humor in this futility, but also romanticism. If photography is a way of gathering or affirming knowledge of the world, what do these proto-photos relay? They are pictures of not knowing, of diligent longing and passing time. Here “brief” and “largely unnoticed” apply to order in the stars, but they also hint at the fleeting inconsequence of one’s own actions and life.

- on and on

As an ongoing series, When the cosmos aligned... provides a methodology but doesn’t make promises. There is no strict rhythm or set duration. The cyanotypes will be made when they are claimed to be until they no longer are. Such open-ended repetition often plays out in Gronsdahl’s work, as a way of continuing and concentrating.

Ways of listening (begun in 2015) consists of hundreds of humble wheel-thrown ceramics.[1] The smoothly curved surfaces remain unfired; fragile and useless for the functions their forms imply. Instead, they offer aural experiences. Held up to an ear, each reveals its own tenor of void, like a distant rushing wind. As with the cyanotypes, there is an element of absurdity. The series presents objects that work against utility and logic, requiring hours of effort at the potter’s wheel to form perpetually empty vessels. In countering expectation, in presenting next to nothing, the vessels ask for deeper consideration of their objecthood, the poetics of their making, and the value of attention paid. They operate not only as individual pieces but also as an undertaking, a volume.

- close readings

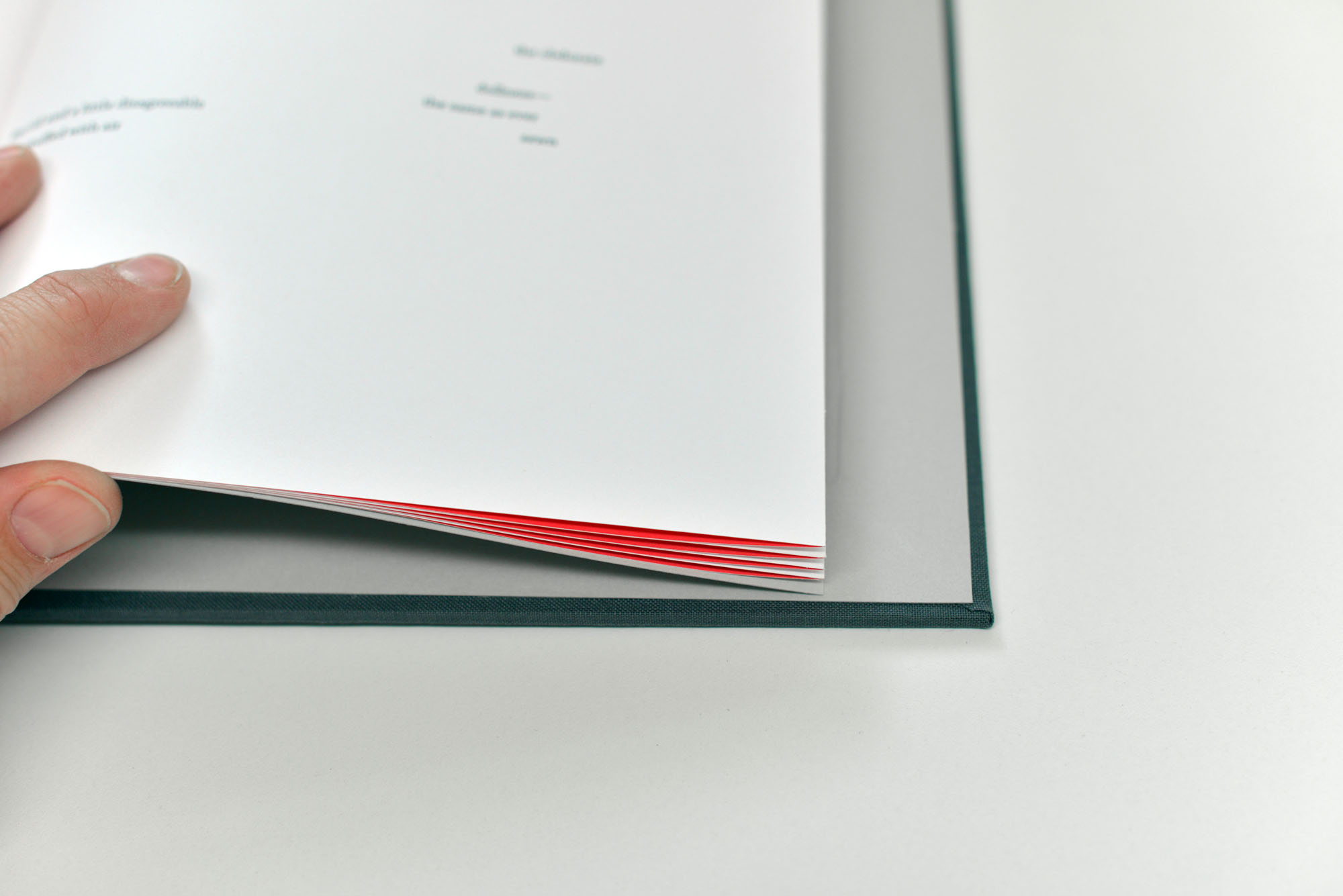

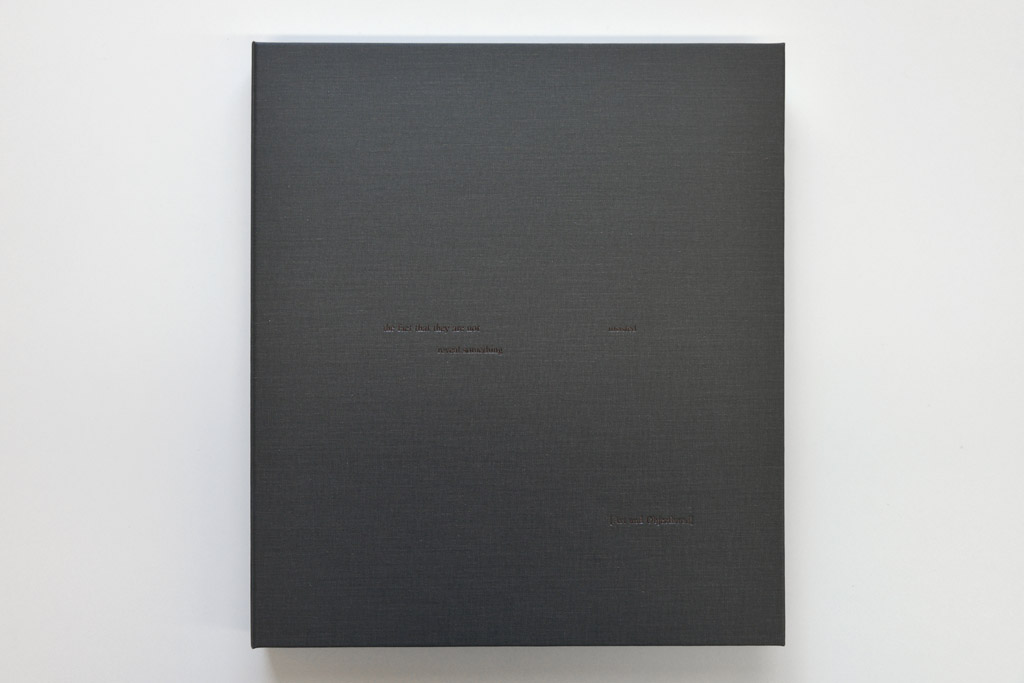

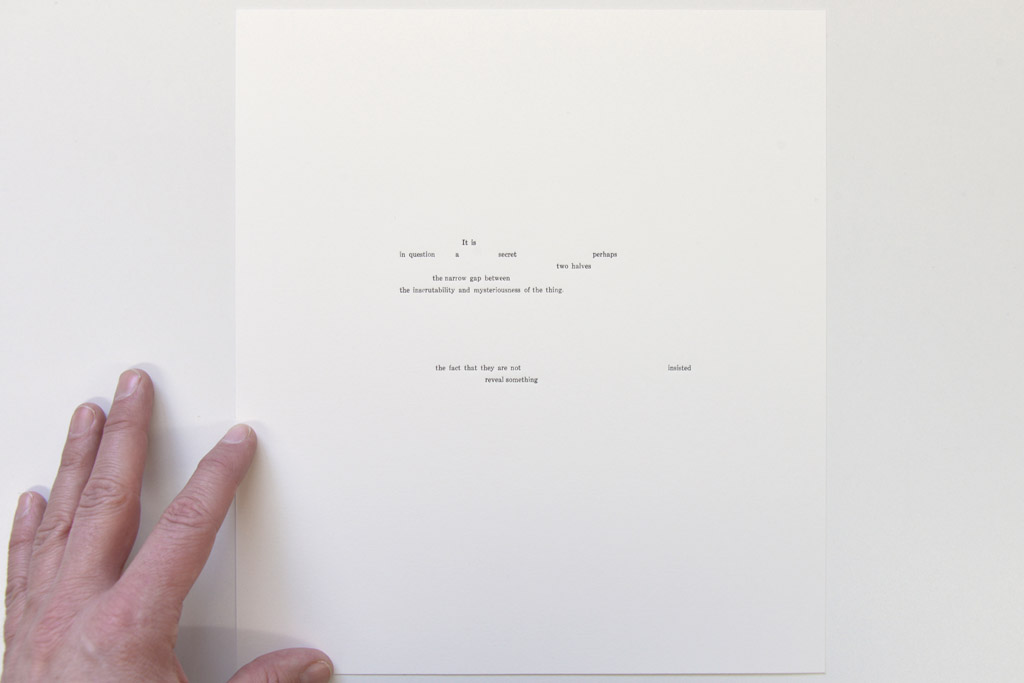

The on-going-ness of Gronsdahl’s serial productions also finds expression in his “remediated texts.” For these he alters the writing of other artists, critics and theorists, erasing most of the originals in order to carve out new compositions. The series began with Donald Judd’s “Specific Objects” (1965), followed by Michael Fried’s, “Art and Objecthood” (1967), and has continued on a slow, anachronistic path through art theory since minimalism.[2] Gronsdahl describes this undertaking as a “fractured, disorienting compendium that sits in contrast to orderly historical narratives.”[3] The altered texts read like poems, fragments of introspective language that float on mostly empty pages. From the first book, The same as the shape of an object [Specific Objects] (2016), this page stands out as a personal annotation, an apt reflection on the manner and process of Gronsdahl’s own work:

Once again/though it would make/no difference/It is as though one/has no duration—/no time at all/to speak/as only partly present/if only one were/more/acute, a single infinitely brief instant would be long enough to see everything.

Even if one is familiar with the sources, and tries to read through understandings of them, there are too many blanks to fill in. Reading them feels like going over the memories of a long-ago day, words smattered on the page like a series of impressions, bits of clarity drawn from a cloud. The remediated texts are personal and idiosyncratic, and in this way emphasize something essential about reading. It is always experiential, a link in a chain, cohering in a moment and dissipating over time. In creating one path through each text, Gronsdahl’s compositions also imply the myriad other paths that could be taken, in a way that “unmediated” texts rarely invite such conjecture. In paring down, they formalise one of an infinite series of possible un-writings/re-readings.

- hardly

Gronsdahl’s approach to art history aligns with his material investigations; both convey a deep curiosity about knowledge, understanding and the ways that we parse meaning from what seems insignificant. Even as these subjects (aesthetics, our place in the universe) are complex and often overwhelming, Gronsdahl broaches them with levity. There is a certain lightness to his work; lightness of touch (the artist’s hands very involved but not in evidence), lightness in material (reduced, responsive), lightness from means to end (spare parameters). This airiness leaves room for soft focus and speculation—even inviting doubt—but it doesn’t equate to effortlessness. There is striving in the repetition and restraint, along with recognition that some things can’t be rushed or overly determined. Reflecting back to the viewer, there is an invitation to take time and care, and a caution—not overlook or over think, less something essential be missed.

– Rose Bouthillier

[1] The title invokes John Berger’s iconic television show and book Ways of Seeing (1972), which explored how people derive meaning from art and images, guided by context, technology and culture. There is a contrast between Berger’s forceful, structured arguments and the quiet reiteration of Gronsdahl’s vessels.

[2] So far other source texts include “Death of the Author” (1967) by Roland Barthes, “Grids” (1979) by Rosalind Krauss, “What Is a Minor Literature?” (1975) by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, and “The Poetics of the Open Work” (1962) by Umberto Eco.

[3] Email to the author, August 15, 2018.

You must be logged in to post a comment.